The Australian government claims the banks are “unquestionably strong”. The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) is given credit for this strength, through its supervision of the banks through the 2008 global financial cri sis, and its subsequent lifting of the banks’ capital from 9.5 to 14.5 per cent of their assets.

If anything, APRA is sometimes criticised for making the Big Four banks too strong and profitable, because it has come at the expense of competition in the banking sector, and the banks’ duty of care for their customers, hence the misconduct and abuses being exposed by the royal commission. APRA ignores such complaints, pointing to its mandated responsibility for “financial stability”—strong, profitable banks, even though an oligopoly, make for a stable financial system.

At least, that’s the story.

Hiding in plain sight is a glaring contradiction to this claim of financial stability, which is Australia’s world-record housing bubble. Australia’s Big Four banks are more exposed to the housing market than were their counterparts in the USA, UK, Spain and Ireland when they suffered banking crashes following the collapse of the real estate bubbles in those nations in 2008. Around 63 per cent of Australian bank lending goes to mortgages—compared with 30 per cent in the USA; between 20 and 30 per cent in the UK and Canada; and 15 per cent in Hong Kong. The borrowing that has fuelled this bubble has driven up Australian household debt to around 200 per cent of annual household income and 120 per cent of GDP.

Not everyone accepts the housing market is a bubble, and that determines their view of the health of the banks. For instance, the government, regulators and banks, which hold that the banks are “unquestionably strong”, all deny the bubble. Those who acknowledge the bubble recognise that the financial system is in fact extremely unstable, and teetering on the edge of a crash that will bankrupt the banks.

Eerie precedent

There are striking similarities between Australia today, and Ireland before its banks crashed in 2008. In the lead-up to the September 2008 global financial crisis, virtually the entire nation of Ireland was euphoric about its economic boom, centred on real estate development. Sound familiar? And 28 per cent of bank lending went to property developers, slightly less to mortgages—combined still less than the 63 per cent of Australian banks’ lending to housing.

One economist, Morgan Kelly, had warned for a year that Irish real estate was a bubble, but his warnings were met with universal denial. Also sound familiar? The denial was so ingrained that when the September 2008 crisis impacted the liquidity in Ireland’s banks, the Irish government announced it was guaranteeing the banks, confident that they were well capitalised and that the guarantee would be enough to see them through the liquidity crunch.

Within weeks the Irish property bubble burst and the banks collapsed. As the government was on the hook for the banks’ losses, the government bailed out the banks, and then itself required a bailout from the EU, which dictated crushing austerity on the people of Ireland.

Early warnings

Among a limited number of organisations and individuals, the Citizens Electoral Council has long warned that Australia’s housing market is a bubble and heading for a crash. As early as 2007, CEC press releases questioned whether one or more Australian banks were in danger of collapse due to the brewing mortgage crisis and their derivatives. Unbeknownst to the CEC at the time, bank regulator APRA had in early 2007 suppressed an internal report which revealed that due to the lowered lending standards APRA had approved, the banks had extended 3.4 times more credit into mortgages than they would have, had they stuck to their previous, higher standards.

The report effectively identified a bubble. It also foreshadowed a sharp rise in mortgage delinquencies, a possible mortgage crash, and a recession. Given that this report coincided with the early alarms in the United States about rising defaults on sub-prime mortgages, it should have spurred Australian authorities to act; instead APRA kept the report secret, and it only came to light in an April 2016 report on ABC 7.30. As it happened, 7.30 observed, the eruption of the global financial crisis in 2008 drove Australian authorities to slash interest rates and pump money into the housing market, which averted the property crash and recession that the report had warned of: “But some say that has merely allowed the problem to get far worse, with mortgage debt doubling since APRA’s alarming research was carried out.” (Emphasis added.)

So where do the banks stand today?

Bubble of lies

The mortgage portfolios of the Big Four banks account for 80 per cent of Australia’s $1.7 trillion mortgage market. At least $500 billion worth of these mortgages are identified as so-called “liar loans”, meaning they were based on false income and expense information.

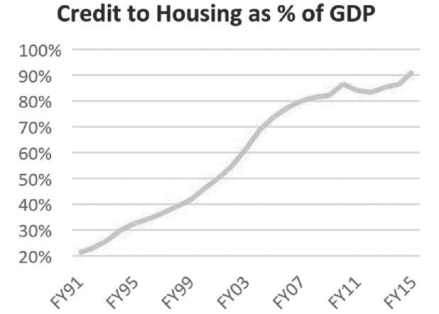

The volume of credit that has gone into housing has soared, creating a

world record housing bubble. Source: John Adams

However, as Denise Brailey of the Banking and Finance Consumers Support Association (BFCSA) insists, and as the royal commission has confirmed, the liars were the banks, not the borrowers—the banks doctored loan applications to record household expenses at the equivalent of the poverty line. An even bigger chunk of these mortgages are interest-only, reflecting the inability of borrowers to repay interest and principal at current house prices.

Interest-only loans reached a peak of 40 per cent of all mortgages in early 2017, following a spike in the rate of interest-only lending that got to almost 50 per cent of mortgages issued in 2016 (compare this with the US rate of interest-only lending before the 2008 crash, which peaked at 25 per cent of mortgages in 2006).

These are official figures, but Denise Brailey reports that the mortgage brokers she surveys reveal that the actual rate of interest-only loans they write is more like 80 per cent. This wave of interest-only loans in recent years is starting to reset to interest and principal, which is almost doubling monthly payments, and that’s before any rise in interest rates. In October 2017 UBS reported its survey that found a third of borrowers with interest-only loans were unaware that their loans were interest-only and they weren’t repaying principal, which sets them up for an even greater shock when their mortgages reset.

Threat of rising interest rates

This mountain of mortgage debt is therefore extremely vulnerable to rising interest rates. According to the latest survey by Finder.com, an extra $100 per month in mortgage payments would push 54 per cent of borrowers over the edge. Martin North of Digital Finance Analytics warned ABC on 11 July that even a 15 basis point (0.15 per cent) rise in interest rates could push a million households into delinquency by September.

The Reserve Bank of Australia’s cash rate is at the record low level of 1.5 per cent, unchanged for the longest period in RBA history. But the best efforts of the RBA cannot shield Australia from rising rates overseas. The banks rely on overseas borrowing for 40 per cent of their funding, and bank liabilities make up the majority of the $465 billion in Australia’s foreign debt that has a maturity of 90 days or less. Therefore when this debt is rolled over every three months, they have to take the interest rate on offer. As foreign observers have been shocked to discover, 80 per cent of Australian mortgages are variable-interest-rate loans, so the higher borrowing costs that the banks incur will be passed on immediately to already overstretched households ‘Unquestionably weak’ capital The truth is that the banks are also dangerously overstretched.

The claim that bank capital is at the “unquestionably strong” level of 14.5 per cent is based on the ruse of “risk-weighting”. This scam allows the banks to claim that only a quarter of their mortgages carry risk, and only hold capital against those mortgages, not all of them. The actual capital of the Big Four banks is razor thin, less than 6 per cent, meaning their leverage of loans to capital is 19 times.

Given that the collateral for 63 per cent of this lending is overpriced housing, an across-the-board real estate market slide of just 10 per cent would wipe out collateral equal to the banks’ capital. Australian house prices have already fallen 4.6 per cent in the last year, and informed observers are anticipating falls of 30 per cent and more. Without collateral backing their loans, the banks would be entirely at the mercy of households making repayments on the liar loans that the banks knew they couldn’t afford in the first place.

Australians are far less likely to default on their mortgages than Americans, due to Australian mortgages being full recourse, meaning the banks can pursue borrowers to the grave; however, there is a limit to what any household can take, and Australian households are reaching that limit. Not only are they already overstretched, but falling prices will trap increasing numbers in negative equity, meaning they owe more than their house is worth.

Such a demoralising plight will trigger outright defaults, especially by the large percentage of “investors” in the market. On top of that, the thousands of job losses in high-paid automotive industries in recent years, and 8,000 high-paid Telstra jobs to go in the next few years, could also trigger a wave of defaults, to be followed by even more as falling house prices flatten the construction industry, which grew into Australia’s second-biggest economic sector on the back of the bubble.

Derivatives

The banks’ bogus capital claims also do not properly reflect their exposure to derivatives, the “notional principal” of which has soared from $14 trillion in 2008, to $40.56 trillion according to the RBA’s latest figures. Most of these derivatives are in one way or another bets on their mortgage lending. Banks always understate their derivatives risk, because they ignore the possibility of extreme events like the 2008 GFC—or a collapse of Australia’s housing bubble.

As unbelievable as it may be, Australia’s financial authorities are not paying attention to this looming danger. A well- placed sourced informed this author that a very senior political-economic expert in Australia in early June asked the RBA if it assesses and manages systemic economic risk, but was informed that was APRA’s job, not the RBA’s. Experts familiar with APRA, however, including former APRA principal researcher Dr Wilson Sy, know that APRA is not assessing and managing risk; in fact, APRA doesn’t even have a research department anymore.

The ruse of risk weighting allows banks to claim they have increased their capital to

the “unquestionably strong” level of 14.5 per cent (top line), whereas actual capital

has barely changed, remaining around 6 per cent (bottom line). Source: Investment Analytics

Conclusion

Banks hold capital as a buffer against possible defaults. APRA has allowed, actually encouraged Australia’s banks to run up a massive exposure to mortgages and mortgage-related derivatives, against razor-thin capital. With borrowers at the extremes of their limits and interest rates rising, there’s no way the housing bubble won’t burst at some point in the near future, and there’s no way that wouldn’t crash the banks. Right now, Australia’s banks are dead men walking, effectively bankrupt.

------------------- ATTRIBUTION -------------------

Citizens Electoral Council of Australia

Postal Address: PO Box 376, Coburg Vic 3058

Phone: 1800 636 432 Fax: 03 9354 0166

Home Page: www.cecaust.com.au Email: cec@cecaust.com.au

Authorised by R. Barwick, 595 Sydney Road, Coburg, Victoria 3058.

Printed by Citizens Media Group Pty Ltd., 595 Sydney Road, Coburg, Victoria 3058. Independent Political Party

11 July 2018

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.